After an unusually strong start to the year, seasonality has caught up with the dry bulk market. Coupled with a slow recovery in global economic activity, it looks set to be another challenging year.

Demand drivers and freight rates

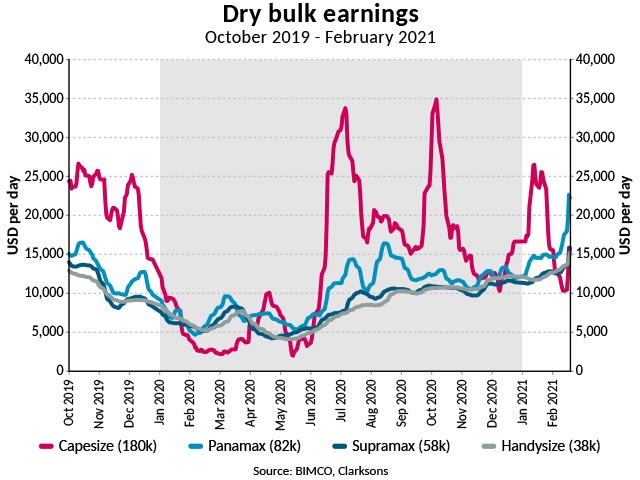

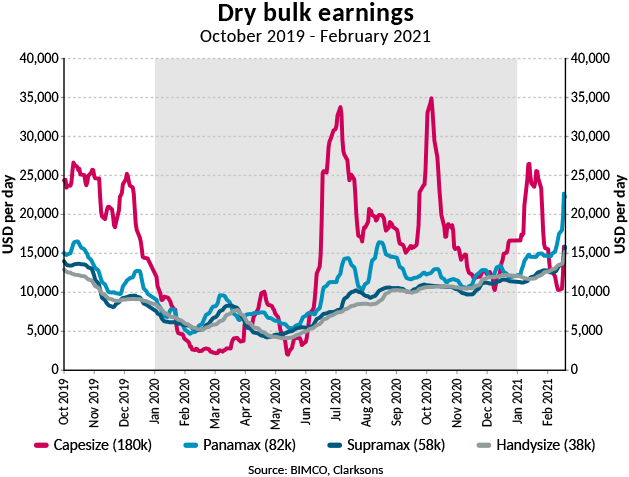

The dry bulk industry has enjoyed an unseasonably robust start to 2021. Average earnings in January were much higher than in recent years, because the usual seasonal slump in cargoes was delayed. However, at the start of February, the Capesize market saw average earnings fall steeply, from around USD 25,500 per day to just USD 12,057 per day on 8 February. After this, they seemed to turn a corner and rose to USD 15,856 per day on 17 February, still well below their break-even level.

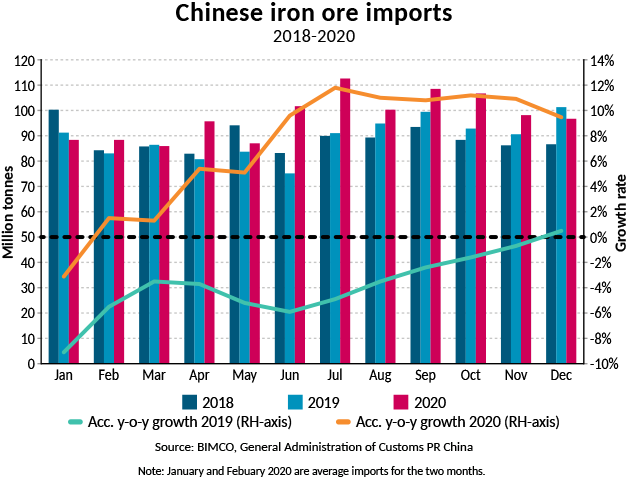

The strong January was in part a result of higher-than-usual demand for iron ore. This led to increased exports and raised prices, from which exporters were keen to profit. These rose to around USD 170 per tonne, their highest level since 2011. Though they remain high, prices slipped back from their mid-January peak at the start of February.

Unlike Capesize ships, earnings for Panamax through to Handysize ships continued to grow in February, with some rising to multi-year highs: Panamax earnings on 17 February stood at USD 22,659 per day, their best since September 2010, and more than double what they need to break even (around USD 10,200 per day); Handysize (38,000 DWT) earnings are at their highest levels in more than a decade, at USD 14,406 per day; and, at more than USD 14,000 per day, Supramax earnings are at their highest levels since Q4 2019.

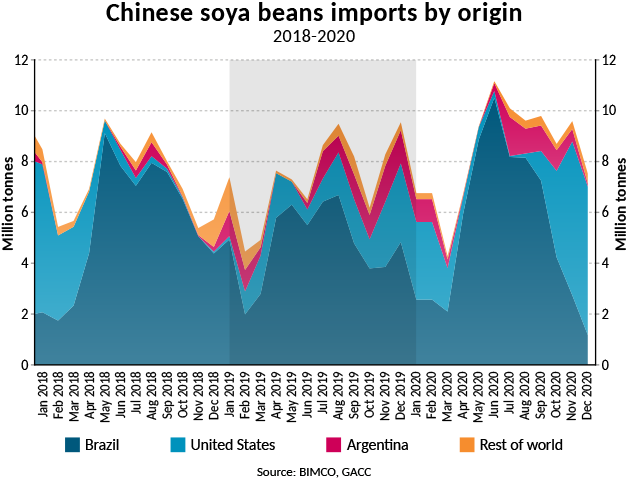

Panamax and Supramax ships have found support in agricultural exports in recent months. US soya bean exports had a very strong start to their season; exports in the first four months (September to December) reached a record high of 39.6 million tonnes, of which almost 94% was transported as dry bulk, and the last 6.3% in containers. This follows strong Brazilian soya bean exports in 2020, up by 12%, compared with 2019, at 83m tonnes.

Total imports by China from these two countries hit a record high of 95.3 million tonnes in 2020 – the equivalent of 1,271 Panamax loads (75,000 tonnes), an increase of 197 loads from 2019. Furthermore, the higher US exports to China means the ratio between Brazilian and US soya bean exports to China has returned to pre-trade war levels. For every tonne of soya beans the US exported to China this year, Brazil exported 1.7, the same as in 2017. In 2018, at the height of the trade war, this ratio was 1:8.3.

In terms of tonne mile demand, average sailing distances for soya beans from Brazil to China are longer than those from the US, though both provide a strong tonne mile boost.

Growth in Chinese demand for soya beans was largely driven by the growth in the nation’s pig herd which, after the mass culling of animals to prevent the spread of the African swine fever, has almost returned to normal levels.

Given the strong seasonality of soya bean exports, a more balanced ratio means that demand for the Panamax and Supramax ships that cater to this trade have their demand spread more evenly throughout the year; as Brazilian cargoes start to drop off in August, the new US export season starts, lasting until the middle of Q1 when Brazilian exports once again pick up.

Coarse grains also provided support to the dry bulk market, with exports from the US, Brazil and Argentina growing 6.1% in 2020. The US increased the most, exporting 47.6m tonnes, a rise of 14.8m from 2019. On the other hand, wheat exports from these three countries fell by 4.6%, a loss of 1.7m tonnes, but this is more than made up for by the growth in coarse grain and soya bean exports.

The red-hot container market has also brought some positives for dry bulk shipping. Some commodities often transported in containers are temporarily being transported as bulk cargoes, as boxes are becoming hard to secure and expensive.

After a strong 2020, the new Brazilian export season, which runs from February to January, is upon us. Because of harvesting delays, it has started more slowly than last year and BIMCO expects exports to fall slightly.

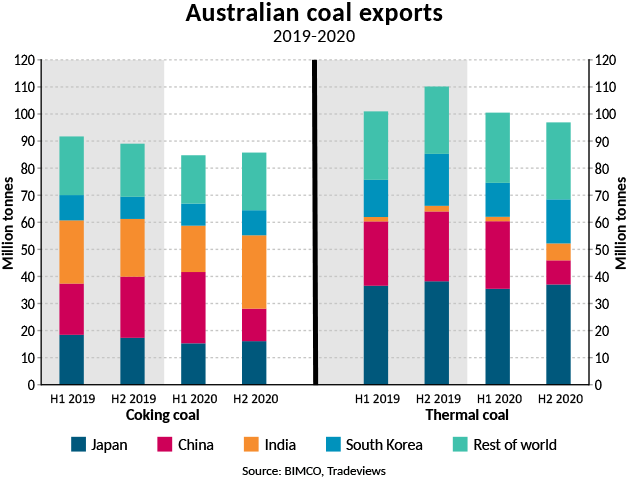

While tensions between the US and China have eased from the height of the trade war, a new spat between China and Australia is now affecting dry bulk shipping. Though Australian iron ore exports remain unchallenged, coal trade between the two countries has seen severe disruption. In 2020, total Australian coal exports fell by 94 million tonnes (-6.1%) from 2019, lowered by the new Chinese import policy and the pandemic, which hurt global coal demand. Exports of thermal and coking coal registered similar drops: down 6.5% and 5.7%, respectively.

So how about exports to China? In the first half of the year they were strong, as its demand recovered much faster than that of the rest of the world. In fact, before import restrictions were put in place, 31.1% of Australian coking coal and 24.3% of steam coal was going to China. However, these figures nosedived in the second half of the year, down to 14.0% and 9.2%, respectively.

India benefited from the drop in China’s share to take 31.6% of Australian coking coal exports in the second half of the year, rising from 20.2% in the first half. No single country saw similar gains in market share when it came to thermal coal, although Japan cemented its top spot, taking 38.2% of Australian exports (from a 35.3% share in H1 2020).

What happened in 2020 meant that, after Q1, the rest of the year saw quarter-on-quarter drops in total Australian coal exports. In Q2, the growth in Chinese imports (up 4 million tonnes), was not enough to make up for losses in the rest of the world. Then, as import restrictions were put in place in Q3 and Q4, the fall in exports to China was larger than the slowly growing demand in the rest of the world. As the distances between Australia and the world’s largest coal importers are similar, the drops in tonne-mile demand have been close to those in tonnes.

Fleet news

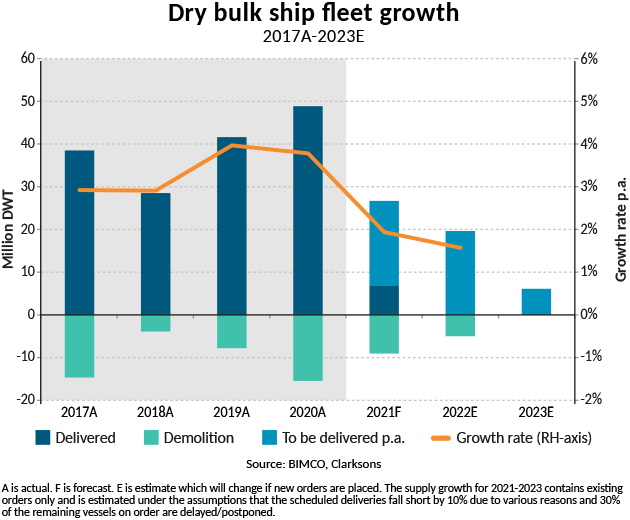

BIMCO expects growth in the dry bulk fleet in 2021 to be the lowest for many years, at around 2%. Lower growth will be as a result of fewer new deliveries; some 27m DWT are expected to arrive – around half of the 48.9m DWT delivered in 2020. Last year, the dry bulk fleet grew by 3.8%. The falling number of deliveries reflects the lower orderbook which, at 51.4m DWT, is almost half that at the start of 2019.

BIMCO expects 9m DWT to be demolished this year, down from 15m DWT in 2020. So far this year, 1.7m DWT have been scrapped. This includes four Capesize ships, three of which were over the ages of 25, including two that were part of the fleet of converted Very Large Ore Carrier (VLOC)s. The renewal of this VLOC fleet is now more or less complete, with new purpose-built ships having been delivered in time to replace the old converted ones.

For demolition to see a meaningful rise, the scrap value of a ship must be higher than its secondhand value. When owners look to get rid of a vessel, they will choose the most profitable option, regardless of the ship’s age. Ultimately, as long as the resale price for a given ship exceeds its scrap value, it will not be sent for demolition. The poor outlook for the sector means secondhand prices are falling, potentially stirring up demolition activity. Given the current market conditions, the value of Capesize ships aged 16 or older are equal to their scrap values.

Outlook

After the strong start to the year, cargoes and tonne-mile demand fell in February, as the Chinese Lunar New Year – despite being celebrated in a different way this year because of the pandemic – lowered economic activity in China. Chinese steel prices fell from their late December peak though, at USD 4,500 per tonne of 20mm steel plate, they are still above the average levels of recent years.

Despite the arrival of the Lunar New Year, the number of spot iron ore cargoes bound for China being offered to the market remained resilient. In the first week of February, there were 10 spot cargoes from Australia and three from Brazil, on a par with levels since the start of the year (source: Commodore). So far, Australian iron ore exports to China remain unaffected by rising trade tensions. Currently, China has little alternative to iron ore but, in the longer term, it may have its sights set on lowering these imports as well. In 2020, Chinese iron ore imports reached a record high of 1.2 billion tonnes, up 9.5% from 2019.

Unlike coal, which China can source from nearby destinations such as Indonesia, Russia and Mongolia, and harming seaborne demand, when it comes to iron ore, other significant sources are harder to find. In the longer term, we could see higher imports from Africa and Brazil, which would boost tonne-mile demand. One of these new sources is the Simandou iron ore mine in Guinea, which has reserves of more than 2 billion tonnes. Though this will add considerable tonne-mile demand, it is unlikely to affect the dry bulk market because the mine will have a ‘conveyor belt’ of purpose-built and long-term chartered VLOCs to fulfil its transport needs.

Another option for the Chinese would be to increase their use of scrap steel, lowering demand for imported iron ore and, by extension, shipping. This has the added benefit of reducing emissions, as China starts on its path towards carbon neutrality by 2060.

After a year of strong growth in Chinese imports, its government’s aim of moving towards a more consumer-driven economy could threaten the continuation of 2020’s high growth in imports of dry bulk goods, which was aided by infrastructure and industry-supporting stimulus measures.

Stimulus packages in the rest of the world have focused more on securing the demand side of the economy – policies that benefit container shipping more than dry bulk. With the crisis still continuing and governments still focused on supporting individual consumers, infrastructure-heavy stimulus projects in many countries still appear a long way off, with no guarantee that they will materialise, and therefore cannot be counted on to provide the fuel for a dry bulk recovery.

Instead, any recovery will be slow and will vary by sector. Demands will increase at different paces, which leaves dry bulk shipping facing another tough year, despite the strong start in the opening months. Overcapacity could once again hamper shipowners’ and operators’ ability to make a profit, especially as currently low bunker prices, which supported profits in 2020, are rising again.

Source: BIMCO