After a down and up year in container volumes, the current logjams in the system and unbalanced trades will take months to resolve, allowing carriers to profit from high freight rates, and tonnage providers to enjoy lofty charter rates.

Once the situation normalises, however – and consumers begin spending more on services and less on goods – structural overcapacity will again become a focal point.

Demand drivers and freight rates

The new year has started on a high for carriers, as the imbalance in the market, congestion in ports, and a general equipment shortage drags on well into 2021. It is a much less positive development for shippers, though; as well as having to pay a much higher base freight rate – and, in many cases, considerable surcharges on top of that – they are seeing long delays in their shipments, causing problems for their supply-chain management.

The current disruptions to container shipping can be attributed to several factors, most importantly the stop-start nature of global container shipping demand in 2020, but also the slower turnaround times in ports as social-distancing measures limit shift sizes among port staff. By mid-February there were 20 containerships at anchorage bound for the port of Los Angeles, a number which in normal conditions is 0. Furthermore, anchorage waiting times are increasing, at around 8 days in mid-February with more ships on their way: around 85% of ships heading to Los Angeles are unable to go straight to berth.

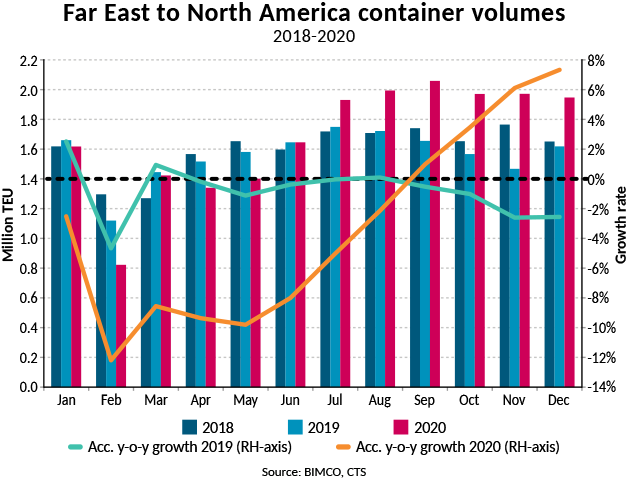

The most obvious example of the disruption the COVID-19 pandemic has caused is US container imports from the Far East. In the first six months of the year, volumes were down by 8.0% on 2019, with every month seeing lower imports than the corresponding month in 2019. The second half of the year was a completely different story. Imports in that period were up by 21.4% from 2019, and more than 1.9m twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU) were imported every month, breaking the 1.8m TEU record that had stood at the start of the year. The new record is 2.1m TEU, recorded when imports peaked in September.

The containerised commodities that have seen the largest increases in US imports from Asia are electronics and furniture, both of which are up by 1.1m tonnes in 2020 compared with 2019. Together, these categories of goods make up 12.8% of total US container imports. An equal share of total imports is achieved by the two other groups of commodities that top the list – namely, plastics and articles of plastic, and machinery.

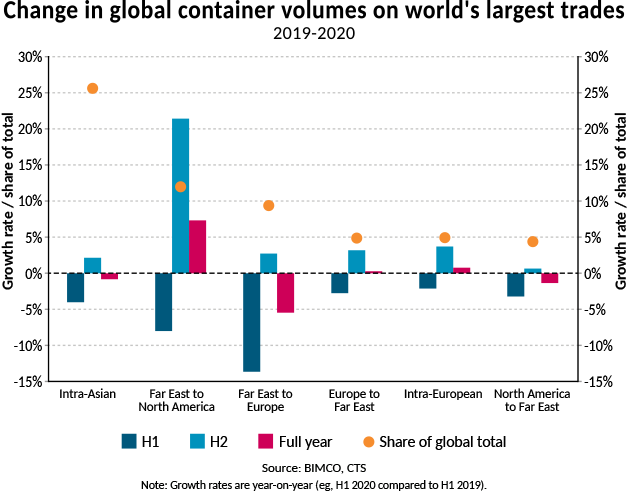

The strong growth in the second half of the year means that total volumes on the Far East to North America trade are up 7.3% this year (1.4m TEU) – and, at 20.1m TEU, they have broken the 20m TEU barrier for the first time. In 2020, volumes on this particular trade accounted for 12.0% of global container demand.

This 12% share is up from 2019, as volumes on other major trades and total global volumes fell in 2020. Globally, seaborne container volumes were down by 1.2% and the two other major trades – intra-Asian and Far East to Europe – also saw volumes fall, by 0.8% and 5.4% respectively. As with the Far East to North America trade, volumes rose in the second half of the year, though the increase was much more muted on the intra-Asian and Far East to Europe trade.

In fact, volumes were up only 2.2% and 2.7% respectively. However, the surge in cargoes to the US, and the stop-start nature of container shipping this year, has led to global issues with the availability of container ships, steep rises in spot rates, a sharp drop in the idle container fleet and, for some ships, a return to charter rates not seen since before the global financial crisis.

Charter rates for a 2,500 TEU ship have risen to USD 20,000 per day, while those for an 8,500 TEU ship now stand at USD 42,000. The high charter rates reflect carriers’ strong demand for extra tonnage and their struggle to find extra ships to help ease the current situation, with red-alert conditions throughout their networks.

There is also anecdotal evidence that carriers are being forced to blank scheduled sailings – not because of a lack of cargo demand, as would usually be the case around the Chinese Lunar New Year, but because of congestion in the import ports. This means some ships are unable to make it back in time for their next scheduled sailings, and the small idle fleet means carriers cannot easily charter in extra tonnage.

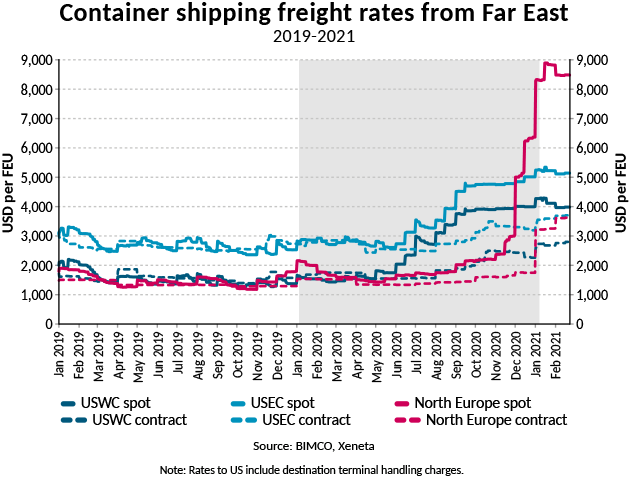

Despite the continued tightness in the market and lack of space for shippers’ containers, spot rates – after their sometimes-meteoric rise – have plateaued. The price of transporting a forty-foot container from the Far East to Europe was around USD 8,500 in the middle of February, while the price for the same box to get to the US West Coast was around USD 4,000 dollars and to the East Coast USD 5,100. Many shippers are still seeing their spot market costs rising, however, as carriers use their leverage to add various surcharges to the base rate, adding up to USD 2,500 per container to the transport costs.

As expected, contract rates are slowly following the lead of the spot market and moving upwards, as carriers, facing high uncertainty, try to adapt to the situation and set themselves up as best as possible for the year ahead. In practice, this has translated into more differentiation between what shippers are being offered. The largest customers, which carriers judge they can’t afford to lose, are more or less seeing prices from last year’s contracts being rolled over into new contracts. However, smaller shippers (still large, but not a must-have for carriers) are being offered higher contract rates – and, in many cases, have been unwilling to sign 2021 contracts at this stage.

Instead, they have been given temporary extensions to the contracts that run through to the end of Q1 2021, to allow more time for longer-term contracts to be negotiated. This is especially the case on trades between the Far East, the US West Coast and Europe. It means that, on these trades, long-term rates are unlikely to stay as high as they are currently once these temporary extensions run out and they agree on new long-term contracts. The new contracts will have higher prices than last years’ contracts, but will be lower than the temporary extensions.

Fleet news

Just as container volumes and spot freight rates set records in the fourth quarter of 2020, so did contracting for ultra large container ships (ULCS). Though no month beat the record 20 ULCSs ordered in September 2018, the 25 ships ordered in Q4 2020, with a total capacity of 0.54m TEU, is the highest quarter on record.

A further 15 15,000 TEU ULCS have been added to the orderbook so far this year. This includes 11 LNG powered ships in two separate deals, all of which will be built in South Korea. In February, another four 24,000 TEU ships were ordered.

All this ordering means the total size of the orderbook – which, for a brief period in Q4 2020, totalled less than 2m TEU (the first time this has happened since 2003) – has come off these multi-year lows, and currently stands at 2.9m TEU, with a total of 352 ships.

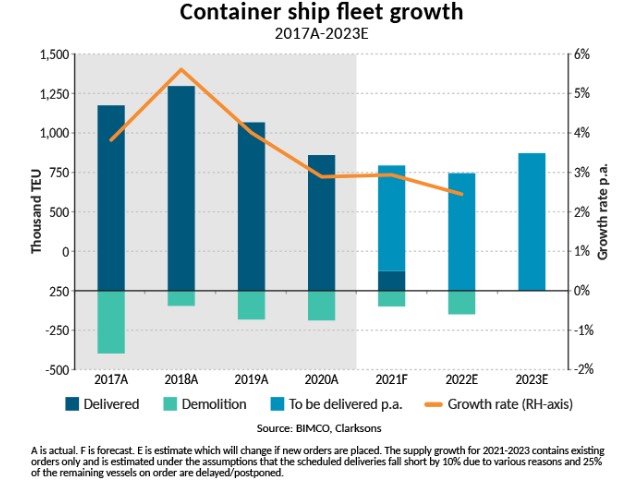

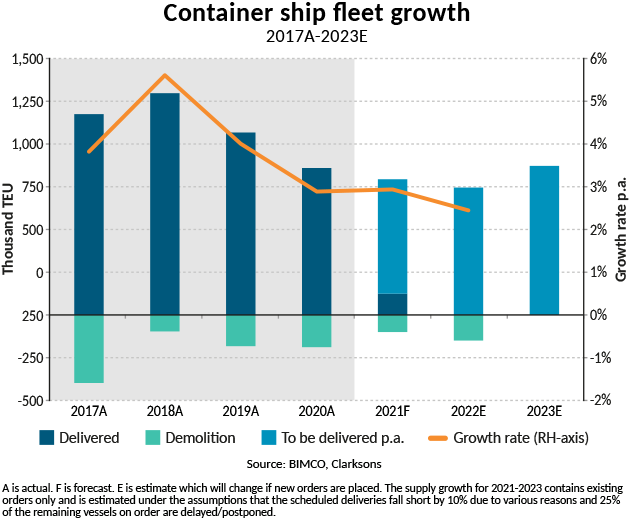

Of these ships on the orderbook, BIMCO expects around 790,000 TEU to be delivered this year, a 7.7% drop from the 857,620 TEU delivered in 2020, which was the lowest level of container ship deliveries since 2004. Of the deliveries expected this year, 124,730 TEU have already been delivered, in the form of 19 feeder ships, with an average capacity of 2,098 TEU, and five neo-Panamax ships totalling 61,760 TEU. There has also been one ULCS delivered – the CMA CGM Rivoli, with a capacity of 23,112 TEU. It is the fifth of nine LNG-powered sister ships, with the remaining four scheduled to be delivered by Chinese yards before the end of April.

As with deliveries, demolition is set to drop this year compared with last year. After a peak in June and July 2020, when demolition yards re-opened after lockdowns, the strong demand for container ships meant that only a handful of feeder ships were demolished in the last months of the year. In total, 188,758 TEU were removed from the market, an increase from 2019, due almost entirely to high demolition in the summer months. BIMCO expects container ship demolitions to total 100,000 TEU in 2021. So far this year only four feeder ships have been demolished totalling 3,707 TEU).

With these expectations, BIMCO forecasts that the fleet will grow by around 3% in 2021, up slightly from 2.9% in 2020.

Outlook

The short-term outlook for container shipping remains positive, as the current backlog of cargoes – and mismatch between where containers are and where they need to be – will not be resolved for months. BIMCO expects carriers to be busy repositioning until at least midway through the year. Furthermore, with the pandemic not yet behind us, and governments still providing support to personal income, spending on goods will continue to be high, promoting demand for container shipping.

Once a wide range of services – including restaurants, themes parks and gyms – re-open, however, and consumers return to spending a larger share of their money on experiences, the share of spending on goods will fall. This shift will be made starker by the fact that many of the goods that have been bought in 2020 are one-off purchases for home-offices, gyms or kitchen improvements, lowering the potential for container imports to continue growing at their current strength.

The long-term contracts currently being negotiated and fixed will provide a solid income stream for carriers throughout the year. As these account for by far the largest share of transported volumes and carrier income, the current strength of the contract market paints a promising picture for carriers’ bottom lines this year, even if rates on the spot market start falling. The tightness in container availability and high prices mean that some commodities, such as grains and forestry goods, have seen a temporary decontainerisation, both on trans-Pacific and intra-Asian trades. Instead, these goods are being sent on dry bulk ships, adding to demand for Handy through to Panamax ships. BIMCO has recently looked deeper into US containerised soya bean exports, which, in the first four months of the 2020/2021 season, accounted for 6.3% of total soya bean exports. BIMCO members can see the findings here.

The current tightness in the supply of container ships will also pass – and although it will happen gradually, by the time the ships that have been ordered in recent months arrive on the water, container shipping will probably have to face up to its overcapacity problem again. If carriers remember the lessons of 2020, however, they will be better able to manage capacity, leaving tonnage providers to soak up more of the losses.

Source: BIMCO